Sophia Opatska is vice-rector for strategic development at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv and the founding dean and chair of the Supervisory Board of Lviv Business school, also at UCU. Opatska was a visiting scholar at the Nanovic Institute for European Studies in 2017-2018 and a participant in the Advanced Leadership Program in Rome in 2022, an initiative of the Catholic Universities Partnership.

On August 24, 2022, Ukraine celebrated the 31st anniversary of its independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Indeed, Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence was part of the reason the USSR fell. When I am abroad — as one of five million Ukrainian refugees or, as some Europeans call us, “unfortunate tourists” — I have an app on my phone that sends push notifications when the air raid siren sounds in Ukraine, specifically in the Lviv region where my husband, son, and parents are living. On Ukrainian Independence Day, I received no less than 14 push notifications over 12 hours, beginning at 6:54 a.m. and ending at 20:30 p.m. At some point after leaving Ukraine in March, I inevitably turned off the sound. I remember doing this one night after we had arrived in Poland and the alarm had woken my younger kids. Can you imagine going through this seven times per day: hearing an alarm that signals an imminent threat to your life and forces you to take shelter, including on one of the most important days for your entire country? Imagine if instead of celebrating with fireworks on July 4, Americans were forced to hide in bomb shelters several times.

At the end of May, my colleagues at the School of Public Management at Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) calculated how much time Ukrainians had spent in shelters, in response to air raid sirens, in the three months between February 24 (the day of Russia’s invasion) and May 24. The now-occupied Luhansk region held the record with 53 days and 16 hours. This was followed by the Kharkiv region, where citizens have been under constant shelling from short distances and have spent 19 days and 17 hours in shelters, then Chernihiv region (16 days and 1 hour), the city of Kyiv (15 days and 13 hours), and Zhytomyr region (14 days and 16 hours). These figures are shocking, even without going deeper into the consequences of constant aerial bombardment: the human lives lost, the psychological damage inflicted upon the people who go through this madness, and the damage to infrastructure, including crucial social infrastructure.

When I started to think about this blog on resilience it became clear to me that I needed to read some articles on the topic. This was partly because it was a buzzword that I had never used before the coronavirus hit the world, but it was also because I realized that so much had happened to me, to my university, and to my nation in the previous six months and I needed a way to sort through this experience and reflect. I realized that the concept of resilience might be helpful to calm the chaos in which we have been operating and bring some perspective.

Five Cs of Resilience

Among the many frameworks for resilience that I found, the most appealing was one that comprises these five elements: community, compassion, confidence, commitment, and centering. These are the “Five Cs of Resilience,” (first developed by Dr. Joel Bennett and his team at Organizational Wellness and Learning Systems) which I think one can identify as important in the life of any Ukrainian nowadays. Allow me to illustrate them with some personal and university stories.

Every year, we ask UCU’s new graduates to describe the university with one word. So far, almost 100% of responses have been: community. This emphasis on community has not been typical of Ukraine, given that the totalitarian system of the Soviet era was designed to kill the very idea. During that period, the alternative was to sit in your small closed apartment on the fifth floor and talk quietly so that no neighbors would overhear you and be able to report you to the KGB. This left us with a society where there was very little trust between citizens. Community, in contrast, is all about trust and openness, even when you are fragile. When a difficult situation arises, it is very important to have the willingness to “face the facts” and acknowledge the reality before you. Are you willing to work within the situation from moment to moment? Are you willing to experience the difficulty, the pain, the heartache, the disruption to your life? But, this willingness may not happen overnight and requires the support of a community, which emerges when other people come to your aid and show you care and concern. I believe that all Ukrainians have by now experienced a sense of community — whether in small circles of family and friends, the nation as a whole, or even on an international level — especially in the most difficult initial months of the war. Community has helped us not only to survive but also, with time, to accept a new reality.

Compassion emerges when you are generous with yourself; you must stop beating yourself up and find ways to be good to yourself before you can show compassion to others. Community and compassion help you through difficulty, which builds your confidence, giving you the “guts” to work it out. When I reflect back to the first two months of the war, the majority of professional Ukrainian women who left Ukraine were beating themselves up for not being able to remain at home and participate in the resistance on the ground. With time and support from each other, we have realized how much we can still do even while we are away from Ukraine, making sure our children are safe. In particular, we can communicate with the international community about Ukraine. The message has to change depending on the place, context, or people we are talking to, but I know that every single conversation, whether it is with one person or a speech to 350 educators, helps my country. I know that I am being just as useful as I would be back home. This realization has given me and many more women the confidence to contribute and confidence in ourselves and in Ukraine’s victory.

Resilience means you learn from your hardships. You don’t just bounce back, you move forward. You make a commitment to keep going. You learn from the past and use those lessons for the future. I recently started a research project in which I talk to Ukrainian business people about their future thinking. Although the interviews are not finished yet and this is just a preliminary observation, I can already identify a common thread in all conversations: a commitment to rebuilding back better and to keep going. This is the case even in scenarios where part of a business is on occupied territory (and is therefore lost), where people have had to relocate, or where their market has shrunk by 70% since before the war. Every single conversation I have with these business people has been focused on opportunities and commitment to these opportunities in addition to the lessons we and the whole world have learned.

Confronting life’s struggles can be stressful to your mind and body, so it’s important to take care of your health. Resilience teaches you to center yourself, to find ways of coping, relaxing, and refreshing. Of course, none of this is easy when you live in a war, your family is in Ukraine, and very close friends, students, and colleagues are involved in the fighting. From UCU, around forty people are at the frontlines. We have lost some close friends and relatives. To keep one's mind in a state that, at minimum, allows you to function day-to-day is a big challenge. For me, being in a community of people allows me to be myself. The Advanced Leadership Program in Rome, organized by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, was one such moment. I felt embraced by colleagues from the Catholic Universities Partnership as we talked about leadership and resilience, bearing in mind the situation the world is in now. Another more recent example is when I participated in an international program about designing a learning environment. On day two, I felt very tired after the stress of seven air alarms on Independence Day. During the morning check-in session, I shared with the group that while I realized we must stretch ourselves in order to learn, I was feeling so stretched by life that, within this group, I just wanted to feel comfortable. This honesty had a positive effect not only on myself but also on the whole group.

When you follow the “Five Cs of Resilience” each one is important, but, according to the framework’s authors, having just one at your disposal can help you cope more easily. That is the thing about resilience: You only need a small seed to grow strong.

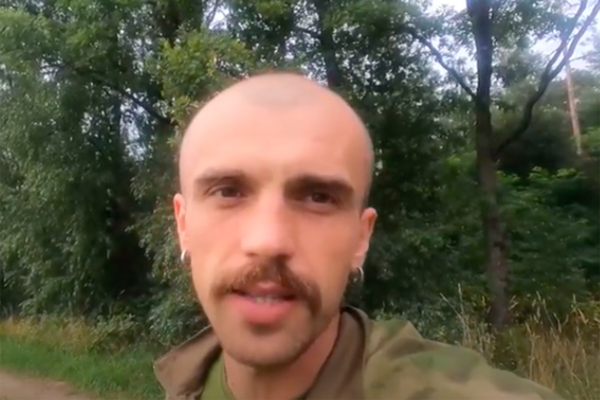

As I was writing, I started to think about UCU faculty, alumni, and students who are on the frontlines these days. Many of them, especially some of the students, were born after Ukraine restored its independence in 1991 but they have turned out to be among the first to defend their nation during the war. Orysya Masna, Alina Mykhaylova, Dmytro Dymyd, Tymur Abdulin, and Maksym Vikarchuk have seen the price of independence. Their example shows that age means nothing if you fight for your family, home, and country, and when you are required to be resilient.